Chapter 2. Health Is a Three-legged Stool

If you are unable to understand the cause of a problem, it is impossible to solve it. – Naoto Kan

IDENTIFYING THE CULPRITS BY ELIMINATION

Our health is determined by three factors and three factors only: Genes, the state of mind, and the environment. Just like a three-legged stool, if one leg is broken or missing then the stool will fall. Of course, other things such as health behaviors (e.g., healthy or unhealthy lifestyles) and economic status (e.g., living conditions) can affect our health too, but they can be seen as elements within the three factors.

It’s convenient for the medical establishment and interest groups to blame the genes for our maladies. The question we have to ask is, has the gene pool of a large population like the US changed over the last 80 years during which chronic diseases have soared? First, the gene pool would not significantly change over just a couple of generations, except for some cases induced by the environment (e.g., radiation exposure and chemical poisoning). And even if some changes have happened, the result would be fewer people getting sick – a process of natural selection.

It couldn’t be more obvious and certain – our genes aren’t the root causes of the soaring chronic diseases.

We all know the state of mind (the condition or character of a person’s thoughts or feelings) is crucial to health. Few would have good health without peace of mind. For the purpose of this book, we focus on stress as a proxy of the state of mind; granted, they aren’t equivalent to each other. As will be discussed in Chapter 11, stress can seriously damage our health by affecting our digestive, nervous, immune systems, and gene expression. However, at the population level, there’s no evidence the stress level in the nation has increased over the last 70 years. On the contrary, existing evidence shows overall happiness has gone up and unhappiness has dropped. For example, the General Social Survey (GSS), started in 1972 by the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) at University of Chicago, shows the percentage of population that was very happy increased from 29.7% in 1972 to 33.3% in 2014, and the percentage of unhappy population dropped from 17.2% to 11.4% during the same period.1

Stress is no doubt a health killer at the individual level, but it’s irrational to believe the overall stress level has increased and is thus responsible for the soaring health crisis around the world.

Taken together, it’s a mathematical certainty that one factor and one factor only is principally responsible for the dramatic rising of chronic diseases, i.e., the environment.

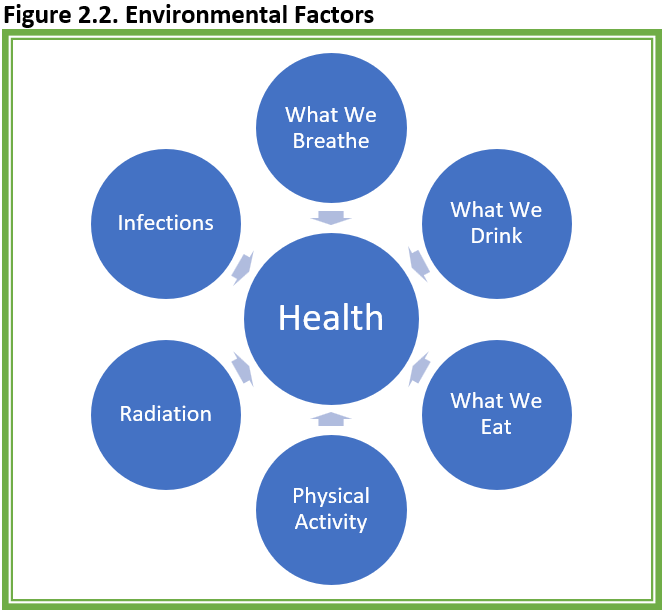

Now, let’s drill down to see what in the environment affects our health. Given the genetic makeup and the state of mind, our health can only be affected by the following six environmental variables or factors:

Of course, our health and even life can be affected by exposure to extreme cold or heat, but can you think of any other factors that can affect our health? So far, it’s not overwhelming, right? After all, it’s only six factors. Now, let’s figure out what roles these six variables play in the unfolding health crisis. It’s getting more complex but will become simpler at the end.

Let’s start with the air we breathe. Without much doubt, the air quality overall across the country has improved since World War II. In addition to the environmental movements, anti-smoking campaigns have also helped. Therefore, air can be ruled out as a major culprit. But every rule has an exception: The quality of indoor air in many homes might have deteriorated, mainly because fire retardants have been added to the padding for carpet, beds, sofas, and chairs etc. These fire retardants aren’t chemically bonded to the materials and can easily escape into the air as dust, which proves to be a health hazard for many (to be discussed in next chapter). Further, more and more other chemicals called VOCs (volatile organic compounds) are polluting our indoor air as more chemicals used in cleaning, disinfecting, cosmetics, degreasing, and hobby products make their way into our homes.

Another exception is the breathing of our skin. Our skin can breathe in or absorb plethora of toxins. We’ve been putting more and more chemicals on our skin – soap, lotions, cosmetics, sunscreen, insect repellants, and detergents on our clothes, to name a few.

The greatest ‘exception’ is the fast-developing countries. A recent study published in Environmental Research revealed air pollution from burning fossil fuels alone causes 10.2 million premature deaths globally each year – 62% of the deaths in China (3.9 million) and India (2.5 million).2

No matter which country, if anything is wrong with what we are breathing, it’s the manmade chemicals or pollutants.

Now, let’s look into what we drink. I used to believe that across the country, the water we drank was good since most of the polluting companies have been kicked out to developing countries. Now I’ve realized our drinking water is not as wholesome as it appears. First, the chemicals such as PCBs and DDT banned decades ago are still in the soil, sediment, and water. Second, a very heavy load of pesticides, such as herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, antimicrobials, insect and animal repellent, have been used in agriculture and residential areas. Where do they go? Nowhere else but in our drinking water. And don’t forget the run-off of fertilizers. Although it’s hard to imagine, the chemicals from prescription drugs and over-the-counter medications, either dumped in garbage cans as leftover or metabolized in our body, are contaminating our drinking water as they go through landfills and wastewater treatment plants. A friend of mine working at a New York State Lab told me the ingredients of all the common medications are detectable in the drinking water.

As if the water weren’t polluted enough, soft-drinks and juices are full of chemicals such as artificial colors and preservatives (will discuss more later).

Again, if anything is wrong with what we drink, it’s the chemicals, manmade or natural.

The ramifications of what we eat is most elusive. Fat, especially saturated fat, was blamed for the epidemic of coronary heart disease (CHD). However, during 1940s-1960s when CHD skyrocketed, the consumption of fat and saturated fat was flat as will be discussed in detail in chapter 4. After the nation started to reduce fat intake and increased consumption of carbs in the 70s, we didn’t see much decrease of CHD incidence but witnessed an epidemic of obesity and diabetes, which put sugar in the spotlight. Yet, the sugar consumption peaked in 1999 and has since declined substantially but obesity and diabetes continue to climb as will be detailed shortly in chapter 5.

Given the opposite trends of chronic diseases relative to fat and sugar, it’s flat-out illogical to believe saturated fat and sugar are the chief drivers of the health crisis and that we can escape this quagmire by cutting fat and sugar intake. Leaving the statistics aside, just look around among your friends, colleagues, and relatives to see how many of them have been carefully watching what they eat and eschew saturated fat and sugar, but are still hopelessly overweight and battling high blood sugar along with other maladies.

That doesn’t mean saturated fat and sugar are innocent – too much saturated fat raises the bad cholesterol level, which may not be the principal cause of CHD but is a risk factor (detailed in chapter 4), and too much sugar is detrimental to our health too (detailed in chapter 5). Health is multifactorial – to fix the problem, we need to separate major crimes from peccadillos.

If the intake of fat and sugar isn’t correlated with the skyrocketing maladies over the last 70 years, then what has changed in our food and been correlated with the disease trend? Again, nothing else except for chemicals (see next chapter for trends and details). Our food including fruits and vegetables are loaded with manmade chemicals. Tests by USDA found 165 different pesticides on thousands of fruit and vegetable samples.3,4 On top of the poisonous herbicides, insecticides, and growth hormones, there are over 10,000 food additives such as preservatives and artificial colors in our food. As if these chemicals weren’t poisonous enough, most processed food is kept in plastic containers known for certain to leach chemicals which are endocrine disrupters and even carcinogenic.

Another compounding factor is micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) have been decreasing in our food because of intensive farming and the explosive growth of fast and processed food as will be discussed in chapters 16 and 17.

In essence, what has changed in today’s food compared to 70 years ago? Chemicals – more manmade chemicals, and less nutrients.

Few would disagree the amount of work-related physical activities overall today is lower compared to 70 years ago – machines have saved us from a lot of hard labor. However, leisure physical activities are a different story. Although there’re no trending data for the last 70 years, for the last 30 years, leisure physical activities have increased for almost every state in the US from 1984 to 2015 according to data reported by the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS),5 the nation’s premiere health survey system run by CDC. Studies from other countries such as Finland and Australia revealed similar findings.6,7 These findings aren’t a surprise – the public has been bombarded by government agencies, professional organizations, and the media with warnings that a sedentary lifestyle is a key factor for all ills. Eating and sitting around too much are indeed unhealthy and some folks do have that bad habit.

Nevertheless, given the leisure physical activity level in the last 30 years has gone up overall rather than down and hard labor may not be good to our health, it’s too far-fetched to claim physical inactivity is the major driver of the unfolding health crisis.

Let’s look at radiation, i.e., ionizing radiation (see chapter 7 for more details). Although it’s only remotely relevant, we need to scrutinize every possibility. First, radiation is mostly related to cancer occurrences. Second, there’s no evidence radiation exposure has increased for the general public in the last 70 years. One exception is the exposure to imaging such as CT and X-rays has increased over the last few decades. These tests are beneficial but not risk free. For example, a study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine in 2016 concluded, on average, annual screening of 100,000 women aged 40 to 74 can prevent 968 breast cancer deaths, but the screening also induces 125 breast cancers leading to 16 deaths.8 In addition, there are some concerns in recent years about the radiation from cell phones and WiFi, but so far there’s no solid evidence linking them to the soaring health problems such as heart disease, obesity, diabetes, autism etc. The deciding fact is that the trends of most of these disorders started to climb well before the widespread use of these devices.

Taking all the evidence together, even in the wildest imaginations, radiation exposure can’t be blamed for the escalation of all the maladies. On the other hand, as will be discussed in chapter 16, too little ultraviolet radiation from the sun resulting in vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency may have played a role in the soaring chronic diseases.

Now, infections. Without any question, the greatest achievement of modern medicine is the conquest of infectious diseases. According to a report from the CDC, the incident rate of 16 common infectious diseases such as tuberculosis and hepatitis dropped from 310 per 100,000 population in 1950 to 50 in 1980.9 Clearly, we can’t blame germs for the escalating health crisis. On the other hand, there’s a popular theory called hygiene hypothesis going around and claiming some diseases such as allergies and autoimmune diseases are a result of too few germs or too clean environment. As will be further discussed in chapter 6, the hypothesis has little or no merit. If anybody still believes in the hygiene theory, just look at the CDC’s report – the rate of infection incidents was 50 per 100,000 population in 1980, and it was 48 in 2016.9 Despite tons of antibiotics, no germs have been put on the list of endangered species.

On the other hand, emerging evidence shows a different kind of infection called dysbiosis (overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria or imbalance of good and bad bacteria in our digestive system) can significantly affect our health. We will go over this topic in chapter 12. In any event, dysbiosis, no matter if it’s improving or worsening over the years, isn’t an independent risk – it can only be induced by our mind and the six environmental factors.

Finally, climate change can affect our health too, but it can only do so through the eight variables or passways listed above (genes, mind, and the six environmental factors). For example, heat waves and violent weather can jack up people’s stress and anxiety, and global warming can alter the ecosystem, which in turn could spur growth of bacteria, viruses, insect infestations, etc. Climate change, unfortunately, will play a larger role in people’s health in the future, but it’s irrational to blame climate change for the soaring chronic diseases, such as heart disease, cancer, obesity, diabetes, autoimmune diseases, and mental health disorders, in the last 70 years.

* * *

We have laid out all the possible factors that could potentially affect our health – mind, genes, and the six environmental factors. Can you think of anything else? If not, the next question is, what is the common denominator in these factors that has been changing along with the prevalence of chronic diseases over the last 70 years?

The inescapable conclusion is: Nothing else but manmade chemicals – we are poisoned slowly and stealthily by all kinds of chemicals, mainly manmade chemicals.

This doesn’t mean high intake of saturated fat and sugar, smoking, drinking, and sedentary lifestyles aren’t detrimental to our health. Anybody indulging in these things will likely get into health problems. But 80 years data have clearly demonstrated these bad habits aren’t the principal drivers of the soaring chronic diseases – public health policies focusing on these bad habits and blaming the victims will not get us out of the epic health crisis.

A BRIEF DETOUR TO CAUSALITY

For sure, the interest groups and unfortunately even many good-hearted but reductionistic scientists won’t accept the causal relationship between chemicals and chronic diseases. They insist observational data only show correlations and causality can only be proven by data from experiments like randomized controlled trials (RCTs). They demand proof of what chemical causes what disease and how. They’re seemingly unaware that even RCTs, the so-called gold standard, are powerless to disentangle the intricate health problems we’re facing today – in addition to ethical issues (researchers cannot deliberately expose half of the study population to harmful chemicals for years) and logistics (placebo controlled and double blind), how can RCTs handle thousands of manmade toxic chemicals interacting in our body? Not to mention, it takes years and even decades for damages to present.

To dispel the causality smokescreen tactics, it’s helpful to take a brief detour to look at the causality theories from a historical perspective.

Although philosophers, epidemiologists, and economists have been fervently working on methods to ascertain causality, there’s no universal standard upon which a causal relationship can be definitively established. In fact, the methods or criteria for ascertaining causal relationships have been changing to fit the problems at hand.

The earliest postulates used to demonstrate a causal relationship between microorganisms and infectious diseases were published in 1890 by Robert Koch (1843-1910), a German physician.10 According to the Koch postulates, for a microorganism to be causal to a disease it must meet four criteria:

- The microorganism must be found in all hosts suffering from the disease, but not found in healthy hosts.

- The microorganism must be able to be isolated from the diseased hosts and grown in pure culture.

- The cultured microorganism must cause the disease when introduced into healthy hosts.

- The microorganism must be recoverable from the experimentally infected host.

These four criteria work perfectly for the causes of some infectious diseases like anthrax, tuberculosis, tetanus, based on which the Koch’s postulates were developed, but fail miserably for other diseases. For example, some people carrying viruses like polio can be very sick while others carrying the same viruses are totally disease free. Koch himself was fully aware of the limitations. Yet, many blind followers rigidly applied the postulates as the gold standard to any causal problem they encountered, which might have impeded the early development of the field of virology.11,12 In fact, it was not until 1937 when Thomas Milton Rivers (1888-1962), the father of modern virology, modify Koch’s postulates to recognize the fact that not every virus carrier is sick and there’s no need to grow the virus in labs.13 In 1957, the postulates were revised again by Robert Huebner (1914-1998), an American physician and virologist, to emphasize the need of epidemiological data to establish causation in viral diseases.14 In ensuing years, the postulates were further refined to ascertain causal relationships between viruses and specific types of diseases, namely immunological, neurological diseases, and cancer.12,15,16

Yet, none of these postulates were found useful when the debate on smoking and lung cancer heated up in the 1950s. Despite mounting observational data showing lung cancer was associated with smoking, the tobacco industry argued the association between smoking and lung cancer was a correlation and it didn’t imply causation. This argument got some traction in the court of public opinion because many lifetime smokers were cancer free. The link between smoking and cancer was further weakened by the fact that cancer could take many years to develop from smoking and may be multifactorial (interacting with other toxins). To break through the tobacco industry’s defense line, RCTs were needed, but it’s unethical to conduct RCTs asking half of the participants to smoke cigarettes for years to come.

So, “in what circumstances can we pass from this observed association to a verdict of causation?” was the question posed by Sir Austin Bradford Hill, professor of medical statistics at the University of London. “Upon what basis should we proceed to do so?” To convict smoking of causing lung cancer, in 1965, Hill published the 9 criteria known as the Hill postulates: (1) strength of association, (2) consistency of evidence, (3) plausibility, (4) coherence of evidence, (5) experimental evidence, (6) analogy, (7) specificity, (8) temporality, and (9) biologic gradient.17

Smoking is believed to meet all these nine criteria and thus was convicted.

Keep in mind, it took decades to nail tobacco smoking, which is just one factor (smoking) and one disease (lung cancer). How long and what postulates will it take to convince the establishment, the policymakers, the media, and the public that we are slowly and stealthily sickened and even killed by thousands of chemicals?

I haven’t seen any postulates specifically proposed to ascertain the causal relationship between chemicals in the environment and the raging health crisis. Obviously, it’s all but impossible to identify all the causal relationships between each of the chemicals and each of the chronic diseases. With existing science and knowledge – reductionist research methods dividing an intertwined giant problem into separated issues and focusing on each of them in isolation would never find consistent results.18 In addition to the fact that nobody knows how thousands of manmade chemicals interact inside our body, it’s very likely that the total toxin burden is what matters rather than a single one, unless it’s an acute poison event.

Nevertheless, with some common sense, it’s not hard to nail the causal relationship between the unfolding health disaster and all the toxic chemicals in totality. As researchers from Johns Hopkins, Stanford, and Harvard Universities explained, “these criteria (or what Hill calls ‘viewpoints’) are not absolute nor does inference of a causal relationship require that all criteria be met. In fact, only temporality is requisite.”19 This statement is absolutely correct and essential. Although temporality or correlation by itself can’t ascertain causality, it can by itself disprove causality. For instance, if the sugar consumption has a downtrend while obesity rate has an uptrend, then it’s illogical to believe sugar is the principal driver behind the obesity epidemic. This elimination process gives us the ability to clear the innocent and identify the real culprit.

In short, after considering all the postulates proposed and used over the last 130 years, to convict toxic chemicals of being the principal culprit behind the soaring chronic diseases, only three criteria are needed:

- It must be scientifically proven the risk factor or factors (chemicals) can pathologically induce the diseases.

- The magnitude and temporal trend of the exposure to the risk factors must be parallel to the magnitude and trend the diseases except for time lags.

- No other risk factors with meaningful magnitude (e.g., number of people exposed) move together with the trend of the diseases.

In essence, this is an identification and elimination (IAE) method, which can be regarded as a summary or simplification of the Hill postulates. It should be noted when assessing the second condition for temporality, time lags need to be considered – it takes time for the diseases to manifest from the initial exposure which typically increases in scale over time, and it takes time for the diseases to subside once the exposure is being mitigated. And the third condition requires sound reasoning and judgement – very often, many things tend to move together. In addition to the consistency of temporality, the nature and magnitude of different exposures need to be taken into account. For instance, too much smartphone use can be detrimental to our health, but we can’t blame that for the unfolding health crisis.

Now, let’s go back to the six risk factors in the environment. What’s the common denominator in them that can adversely affect our health and satisfy the three conditions? It’s the chemicals in totality, plain and simple – it’s the chemicals as pesticides sprayed on everything we eat and also polluting our drinking water, it’s the chemicals in plastics in everywhere, it’s the chemicals added to our food and drink, it’s the chemicals in the household products such as detergents, clothing, sunscreens, lotion, and cosmetics, it’s the chemicals in carpet and padding, it’s chemicals in the furniture, it’s the chemicals in kids’ toys, it’s the chemicals in the building materials – It’s these chemicals sneaking into our body whenever we eat, drink, breathe, and touch.

It’s these manmade chemicals in totality that bring us so much convenience and prosperity, but at the same time sicken and kill us. As Rachel Carson’s feared – Silent Spring has evolved into four-season perpetual widespread human suffering.

References

- University of Chicago. General Social Survey Final Report. Trends in Psychological Well-Being, 1972-2014. April 2015. http://www.norc.org/PDFs/GSS%20Reports/GSS_PsyWellBeing15_final_formatted.pdf

- Vohra K, Vodonos A, Schwartz J, et al. Global mortality from outdoor fine particle pollution generated by fossil fuel combustion: Results from GEOS-Chem, Environmental Research, Vol195, 2021,110754, ISSN 0013-9351, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.110754.

- https://www.ewg.org/release/apples- top-dirty-dozen-list-fifth-year-row#.W4L8xuS0VPY. (Apples Top Dirty Dozen List for Fifth Year in a Row)

- https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/2019PDPAnnualSummary.pdf (USDA Pesticide Data Program)

- An R, Xiang X, Yang Y,Yan H. Mapping the Prevalence of Physical Inactivity in U.S. States, 1984-2015. PLoS One. 2016; 11(12): e0168175. Published online 2016 Dec 13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168175.

- Borodulin K, Laatikainen T, Juolevi A, Jousilahti P. Thirty-year trends of physical activity in relation to age, calendar time and birth cohort in Finnish adults. Eur J Public Health. 2008 Jun;18(3):339-44.

- Chau J, Chey T, Burks-Young S, et al. Trends in prevalence of leisure time physical activity and inactivity: results from Australian National Health Surveys 1989 to 2011. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2017 Dec;41(6):617-624.

- Miglioretti DL, Lange J, van den Broek JJ, et al. Radiation-Induced Breast Cancer Incidence and Mortality From Digital Mammography Screening: A Modeling Study. Ann Intern Med. 2016 Feb 16;164(4):205-14.

- https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/contents2017.htm?search=Infectious_diseases

- Evans AS. Causation and disease: a chronological journey. The Thomas Parran Lecture. Am J Epidemiol. 1978 Oct;108(4):249-58.

- Brock TD. Robert Koch: a life in medicine and bacteriology. 1999. Washington DC: American Society of Microbiology Press. ISBN 1-55581-143-4.

- Evans AS. Causation and disease: the Henle-Koch postulates revisited. Yale J Biol Med. 1976;49 (2): 175-95.

- Rivers TM. Viruses and Koch’s Postulates. J Bacteriol. 1937 Jan;33(1):1-12.

- Huebner RJ. The virologist’s dilemma. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1957; 67(8):430 -438.

- Evans AS. New discoveries in infectious mononucleosis. 1974; Mod. Med. 1:18–24.

- Johnson RT, Gibbs CJ. Editorial: Koch’s postulates and slow infections of the nervous system. Arch Neurol. 1974 Jan;30(1):36-8.

- Hill AB. The environment and disease: association or causation? Proc R Soc mMed. 1965 May;58:295-300.

- Plowright RK, Sokolow SH, Gorman, ME et al. Causal inference in disease ecology: investigating ecological drivers of disease emergence. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. First published: 01 October 2008. https://doi.org/10.1890/070086

- Glass TA, Goodman SN, Hernán MA, Samet JM. Causal inference in public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2013;34:61-75.